Afroeurasia, Not Afro-Eurasia

Discussion of why I spell Afroeurasia without a hyphen

Table of Contents

Every few months, someone asks me why I don’t hyphenate Afroeurasia. Most world history publications use Afro-Eurasia, but I dropped the hyphen after reading the introduction to Ross Dunn and Laura Mitchell’s Panorama: A World History. The textbook is out of print but will be published again with a new publisher. In the meantime, Dunn and Mitchell happily agreed to let me share an edited version of their introduction.

I used this excerpt with my students at the start of the school year to encourage them to reflect on how we, as historians, have power in the names we choose. Using Afro-Eurasia with the hyphen emphasizes the otherness of Africa. Afroeurasia emphasizes the integration of Africans into a large connected macro-region that has historically been integrated, culturally and economically. We also have choices about the terms we use to identify people and places. We can impose our inherited Eurocentric understanding on people and places or use the names people prefer to call themselves and where they live (e.g., Melaka rather than Malacca). In an era of divisive, hyper-nationalist rhetoric from politicians, using Afroeurasia is a small step in emphasizing our shared humanity.

Edited Version

Schoolbooks still teach that there are seven primary land masses, or contents: Africa, Antarctica, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, and South America. In our view this convention needs rethinking. If we accept even a loose physical definition of a continent as a distinct land mass surrounded, or nearly so, by water, Europe and Asia do not separately qualify. No significant waterway or other partition divides the eastern side of Europe from the western side of Asia. Rather the two places constitute, and have constituted for millions of years, a single great land mass. A little more than a century ago, scholars named this land mass Eurasia. Since then, many have recognized that the standard physical definition of a continent properly applies to it. Logically, then, Europe is a long peninsula at the far western end of Eurasia, that is, a subcontinent roughly comparable to South Asia (Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan), a peninsula that juts south.

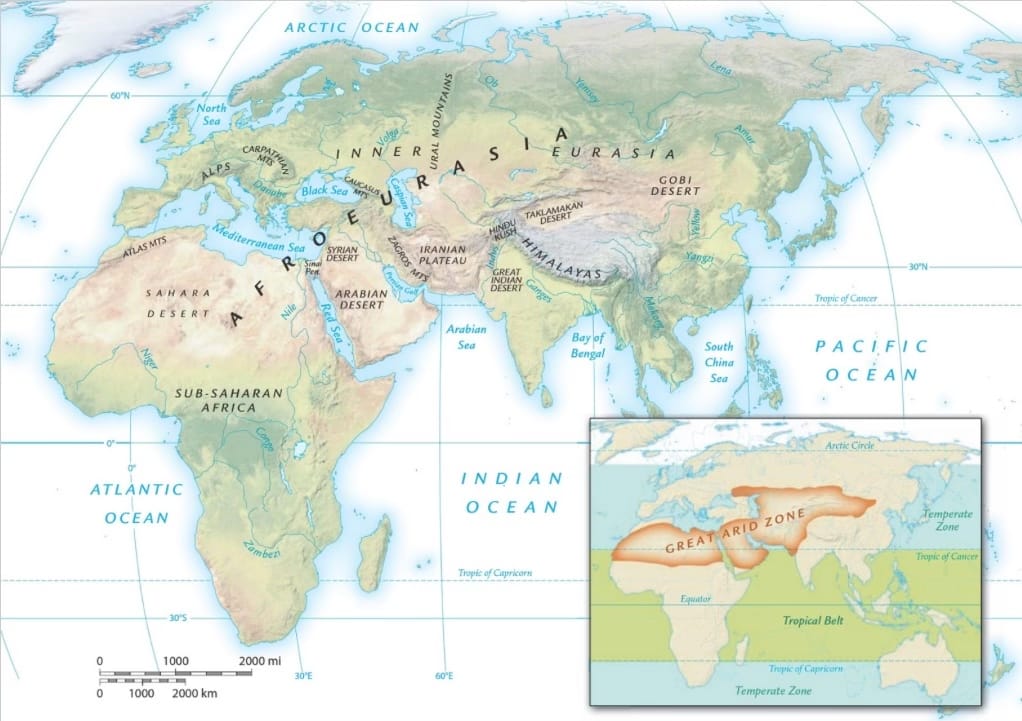

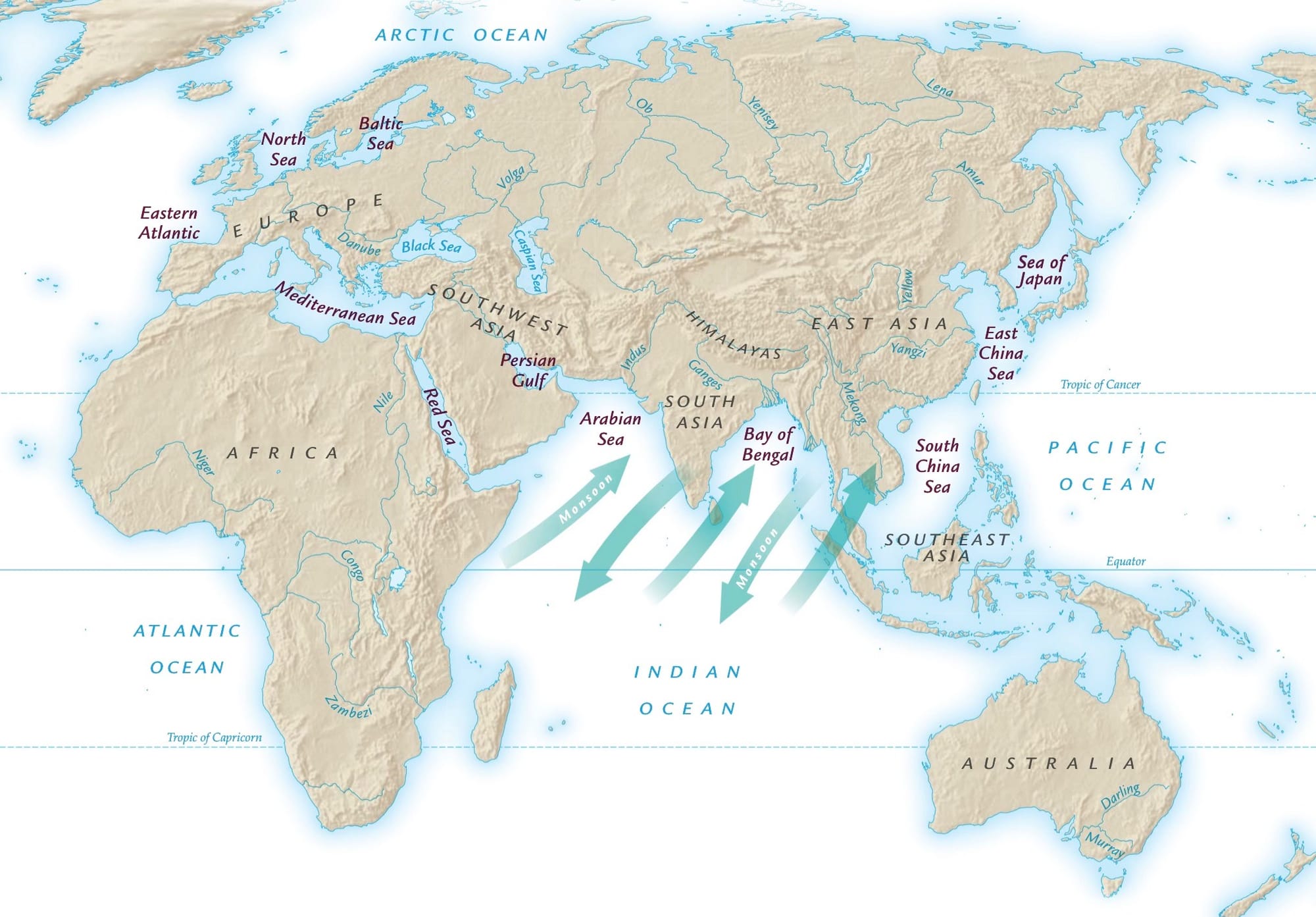

Accepting the idea of Europe as an integral part of geophysical Eurasia, students of global history should find it easier to conceive visually of that entire land mass from the North Atlantic to the North Pacific as a continuous stretch of territory within which humans have lived, migrated, fought, and traded for many thousands of years. But what about Africa? Because it is separated from Eurasia only by the Mediterranean and the Red Seas, it qualifies as a continent by the conventional definition, though barely. Africa also rests on one of the large section of the lithosphere known as the African Plate. Is it possible, nevertheless, to conceive of Eurasia and Africa together constituting one continent? Look at the map. Cover up the Mediterranean Sea with the thumb of your left hand and place the index finger of your right hand over the Red Sea. Notice that with those two seas covered, it is not hard to see Eurasia and Africa together as a single land mass, and one much bigger than Eurasia alone. Compared to the Atlantic or Pacific Ocean, the Mediterranean and the Red Seas are merely "lakes." Humans have been shuttling routinely back and forth across them for thousands of years. And it is worth noting that one can walk from Africa to Eurasia by crossing the Sinai Peninsula and one of the bridges that spans the Suez Canal.

Because of regular interaction among peoples living around the rims of the Mediterranean and the Red Seas, historical developments in Africa, Asia, and Europe have been intertwined far more intensely than the conventional continental divisions would encourage us to think. In other words, an integrated approach to world history demands that we visualize not only Eurasia as a whole but Africa and Eurasia together (plus the adjacent islands or island groups like Japan, the Philippines, and Britain) as a single space within which important historical developments have taken place from very early times.

In fact, ancient scholars had no trouble imagining Africa, Asia, and Europe together as constituting a larger interconnected whole. The Romans called it the Orbis Terrarum, or the "circle of the world." However, the three-continents scheme, a product of human invention to start with, has become so standardized in schoolbooks as the "right" way to see the world that modern geographers have never settled on a label for all of Africa and Eurasia together. In the sixteenth century the term "Old World" appeared in European languages to distinguish the land masses of the Eastern Hemisphere from the "new World," that is, the Americas. These terms, however, are vulnerable to criticism because the Americans were only "new" to the Europeans who first visited them, not to the people who had been living there for thousands of years. In this book we adopt the single world Afroeurasia to express the continuum of lands comprising Africa and Eurasia. It will serve as a convenient geographical tool for discussing large-scale historical developments that cut across the conventionally defined continental boundaries.

Afroeurasia takes up nearly 60 percent of the surface of the earth that is not water. This land mass is not only the biggest one on the planet, it is also where the human species first evolved (as far as we know), and it has historically been home to most of the humans who have ever lived. Today, about 86 percent of the globe’s population inhabits Afroeurasia.

You can also download a more extended version of their discussion of geography and naming conventions. Thanks to Ross Dunn and Laura Mitchell for letting me share their work. Both are excellent people and world historians.

Liberating Narratives is written by Bram Hubbell. If you’ve valued reading this post, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your financial contribution supports independent, advertising-free materials for teachers. Thank you, friends.

If you would like, please forward this message to a friend or colleague and let them know where they can subscribe. (Hint: it's here.)

If you have any comments or suggestions, please share them with me or post them below. I can also be reached on Bluesky, Threads, Facebook, Instagram, Mastodon, and email.

Liberating Narratives Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.