“As a United Nation”: Teaching Black and Indigenous Participation in the Spanish American Revolutions

Discussion of Black and Indigenous involvement in the Spanish American Revolutions.

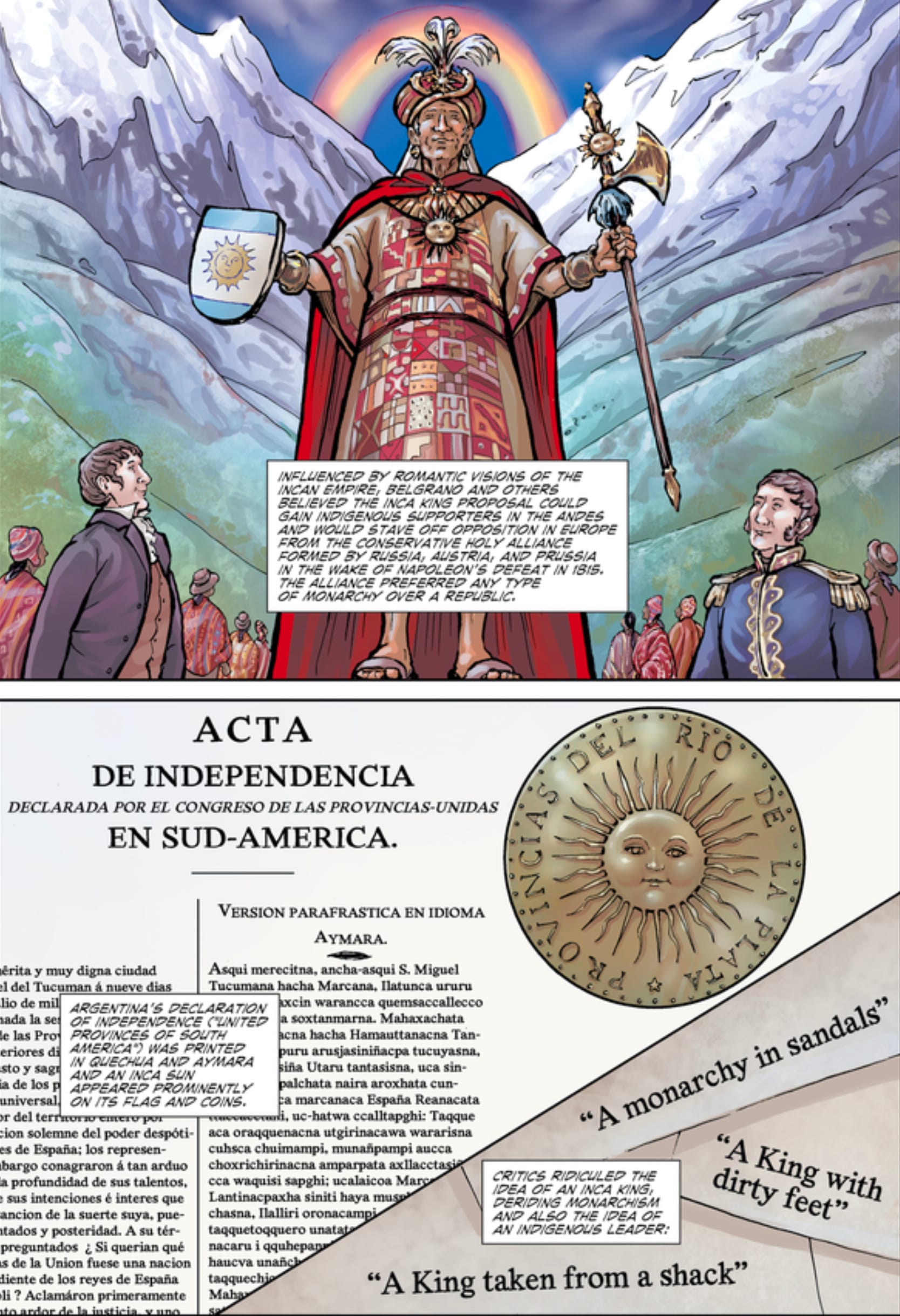

In 2015, I visited Argentina. On my flight there, I noticed the sun on the country’s flag and looked up its meaning in my guidebook. The sun on the flag is known as the “Sun of May” (Sol de Mayo), referring to the country’s revolution that began in May 1810. I didn’t bother to investigate further and quickly forgot about the symbol.

In my first post about the Age of Revolutions, I discussed Charles Walker’s excellent graphic history of Tupac Amaru’s brother, Witness to the Age of Revolution: The Odyssey of Juan Bautista Tupac Amaru. I initially focused on Walker’s short history of the Tupac Amaru uprising in 1780 but didn’t say much about his brother Juan Bautista. The Spanish imprisoned Bautista after the uprising, and he spent nearly forty years in Spanish prisons in South America, Cadiz, Spain, and Ceuta on the North African Coast. The Spanish released him in 1821. Juan Bautista went to Buenos Aires, where he was surprised to learn that many South American revolutionaries wanted to emphasize their Indigenous connections, including the sun on the Argentine flag. That “Sun of May” was the sun associated with Inti, the Incan sun god.

Looking at Walker’s book, I saw the same sun on the Argentine flag. I wondered why we don’t teach more about the influence of Indigenous Americans on the South American Revolutions. In today’s post, I will discuss how we can broaden our approach to teaching the Spanish American Revolutions and better integrate Black and Indigenous experiences.