“Every Continent is Affected”: The Forty Years’ War and Decolonizing How We Teach the World Wars

Discussion of teaching the world wars from a global perspective

It’s hard to imagine any world history course covering the twentieth century without including the world wars. We all know the standard topics we cover for each war. For the First World War, we talk about the assassination (I’m guessing I don’t even need to say the assassination of whom), total war, and the trenches. For the Second World War, it’s a little more personality driven with Hitler, Stalin, Chamberlain and his unfortunate assessment of the Munich Agreement, Churchill, and Roosevelt. Sprinkle in a little Blitzkrieg, Holocaust, and Pearl Harbor. Some readers might think I’m flippant, but we should ask ourselves how often these specific topics and people were the ones we focused on when teaching the wars. When was the last time we challenged ourselves to completely rethink how we teach world wars? For most of my teaching, the only challenge with teaching the wars was figuring out how to fit each one into a single class period. I never worried about what I was teaching.

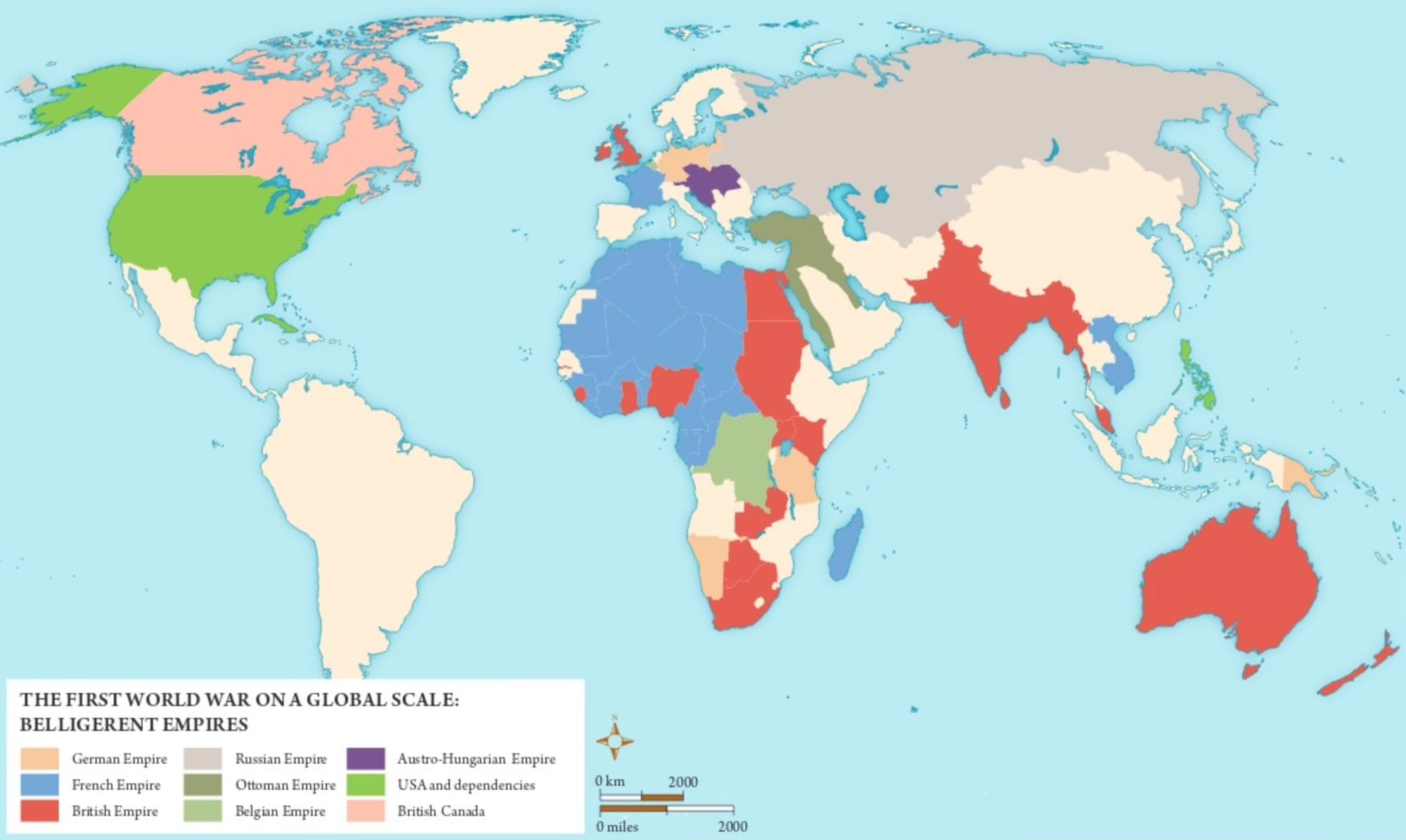

With the centennial anniversary of the First World War, new scholarship and popular articles challenged us to include more Asian and African perspectives. Including missing voices makes sense. During the Paris Peace Conference, even British Prime Minister Lloyd George recognized the Great War was a global war:

The task with which the Peace Delegates have been confronted has indeed been a gigantic one. No Conference that has ever assembled in the history of the world has been confronted with problems of such variety, of such complexity, of such magnitude, and of such gravity. The Congress of Vienna was the nearest approach to it. You had then to settle the affairs of Europe. It took eleven months. But the problems at the Congress of Vienna, great as they were, sink into insignificance compared with those which we have had to attempt to settle at the Paris Conference. It is not one continent that is engaged—every continent is affected. With very few exceptions, every country in Europe has been in this War. Every country in Asia is affected by the War, except Tibet and Afghanistan. There is not a square mile of Africa that has not been engaged in the War in one way or another. Almost the whole of the nations of America are in the War, and in the far islands of the Southern Seas there are islands that have been captured, and there are hundreds of thousands of men who have come to fight in this great world struggle.

I suspect that readers of Liberating Narratives added some new Asian and African examples to what they were teaching, but what did you choose to leave out? How much did slightly expanding the scope of who gets included fundamentally change the story of the wars, or were those African and Asian examples the equivalent of the textbook’s sidebar?

At the 2024 AHA Annual Conference in San Francisco, I attended a panel on Globalizing the Second World War that challenged me to rethink how I taught that war. I was familiar with alternative starting points for the war, but the speakers discussed alternative ending dates and different ways of framing the war. I left that panel happily feeling I needed to rethink how I approach the world wars. We need to do more than simply add more African and Asian participants to older Eurocentric narratives; we need to reconsider how the global nature of these wars forces us to construct new non-Eurocentric narratives.

During the next month, I’ll discuss how we can decolonize our teaching of the world wars. We need to develop new narratives that don’t privilege the European and American experiences of the wars. Instead of considering them two separate wars, we can imagine them as a single, extended conflict. We can use new sources to teach themes that will be familiar. Most importantly, we need to introduce a much greater diversity of individuals whom students learn about. Sprinkling in a few new case studies on the margins of predominantly White, Eurocentric narratives of the wars isn’t enough. It’s time to teach meaningfully “how every continent (was) affected.”

Eurocentrism and When the Wars Were Fought

The first way to rethink how we teach the World Wars is by reconsidering when they happened. Most of us grew up learning that the First World War was from 1914 to 1918, and the Second World War was from 1939 to 1945. A few textbooks might suggest 1937, when Japan invaded China, as the start of the Second World War. These traditional dates for the war reflect when all Europeans went to war with each other, but is that the best way to think about “world” wars?

In the past two decades, excellent scholarship has proposed alternative periodizations for the world wars. In 2014, Robert Gerwarth and Erez Manela published “The Great War as a Global War: Imperial Conflict and the Reconfiguration of World Order, 1911–1923.” Later that year, they expanded the article into Empires at War: 1911-1923. From both titles, we can easily see their emphasis on imperialism and longer chronology of the war. In the article, they provide a helpful summary of their arguments:

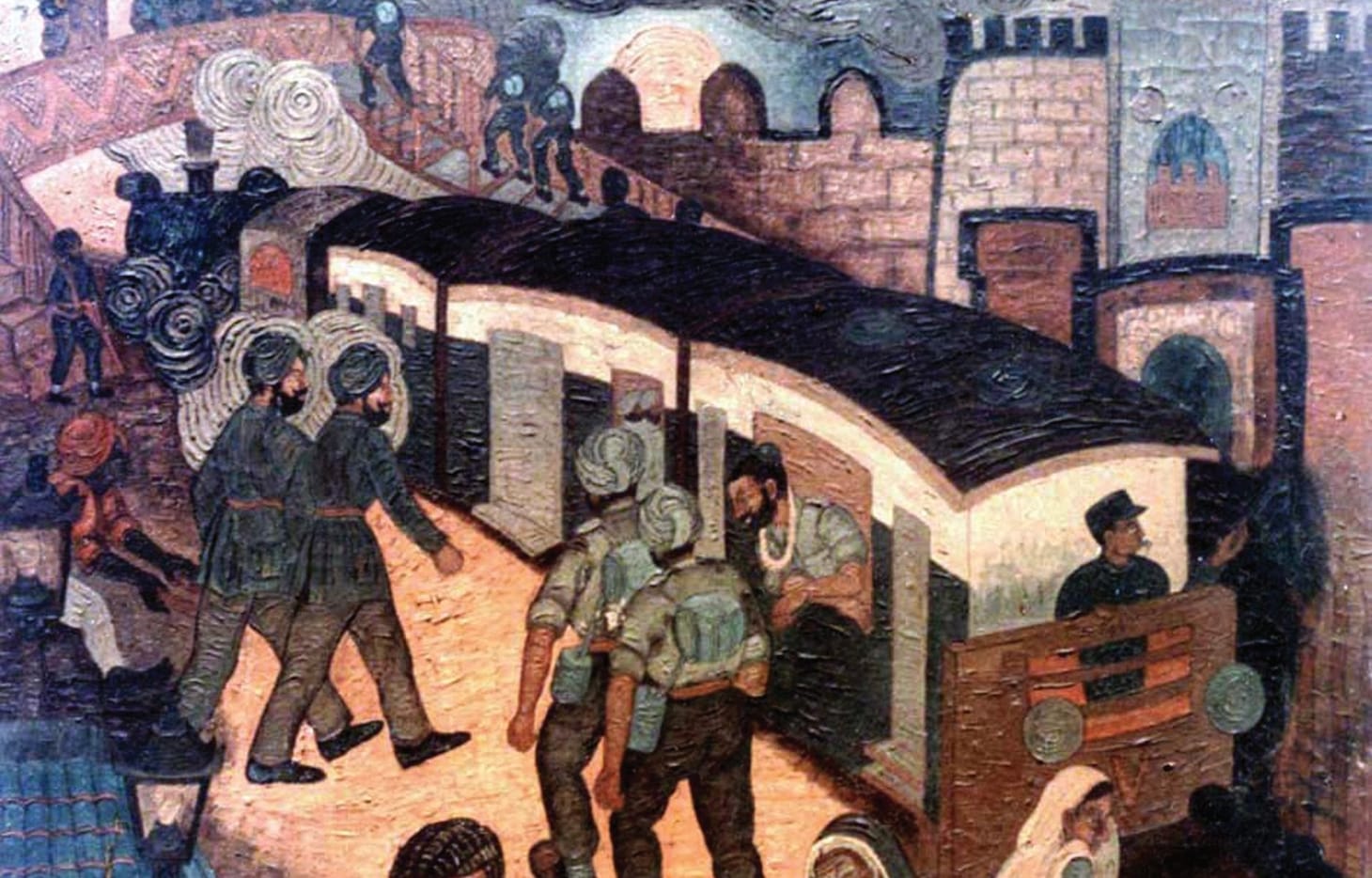

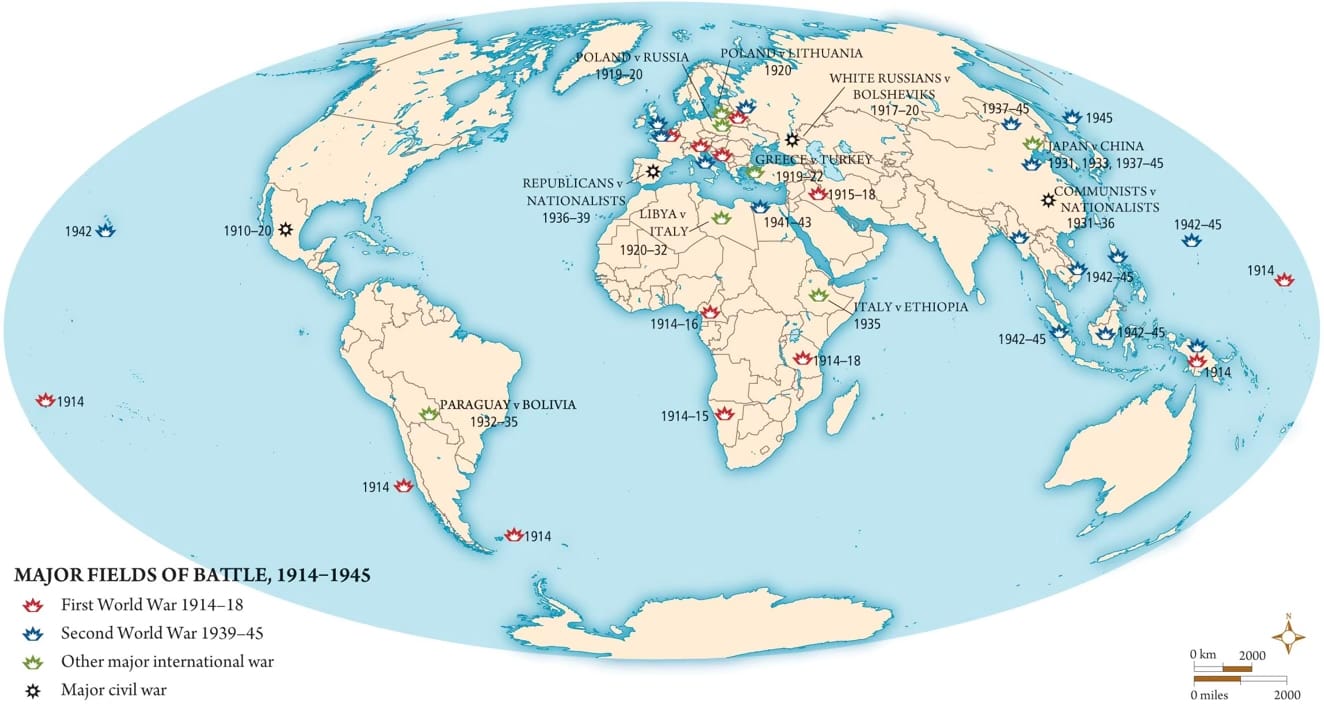

The first premise is that we must examine the war within a frame that is both longer (temporally) and wider (spatially) than the usual one. This move will allow us to see more clearlythat the paroxysm of 1914–1918 was the epicenter of a cycle of armed imperial conflict that began in 1911 with the Italian invasion of Libya and intensified the following year with the Balkan wars that reduced Ottoman power to a toe-holding Europe. Moreover, the massive violence triggered by the conflict continued unabated until 1923, when the Treaty of Lausanne defined the territory of the new Turkish Republic and ended Greek territorial ambitions in Asia Minor with the largest forced population exchange in history until the Second World War. The end of the Irish Civil War in the same year, the restoration of a measure of equilibrium in Germany after the end of the Franco-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr, the decisive victory of the Bolshevik regime in Russia in a bloody civil war, and the reconfiguration of power relations in East Asia at the Washington Conference, were all further signs that the cycle of violence, for the time being, had run its course.

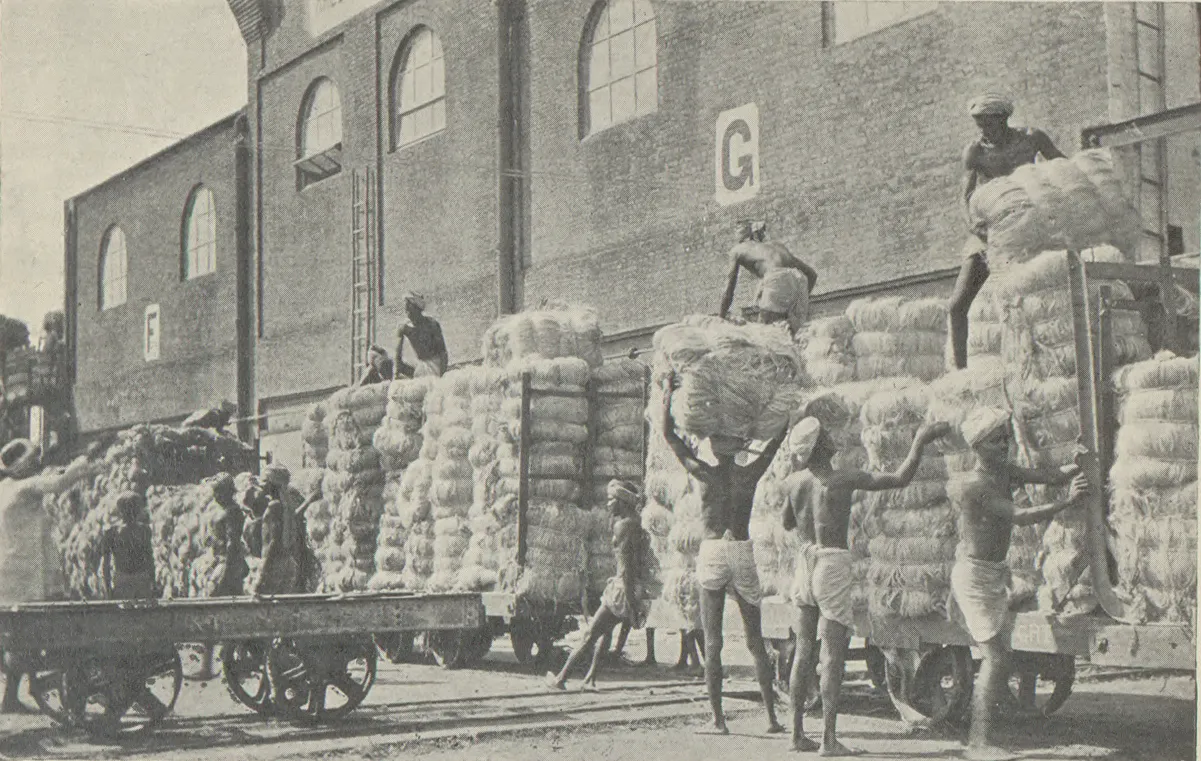

The second contention of this essay is that we should see the First World War not simply as a war between European nation-states but also, and perhaps primarily, as a war among global empires. If we take the conflict seriously as a world war, we must, a century after the fact, do justice more fully to the millions of imperial subjects called upon to defend their imperial governments’ interest, to theaters of war that lay far beyond Europe including in Asia and Africa and, more generally, to the wartime roles and experiences of innumerable peoples from outside the European continent.

Andrew Buchanan acknowledged the influence of Gerwarth and Manela and made similar arguments about the Second World War. In 2019, he published World War II in Global Perspective, 1931-1953: A Short History. He also published “Globalizing the Second World War” in 2023. In the article, he provides a helpful summary of his periodization:

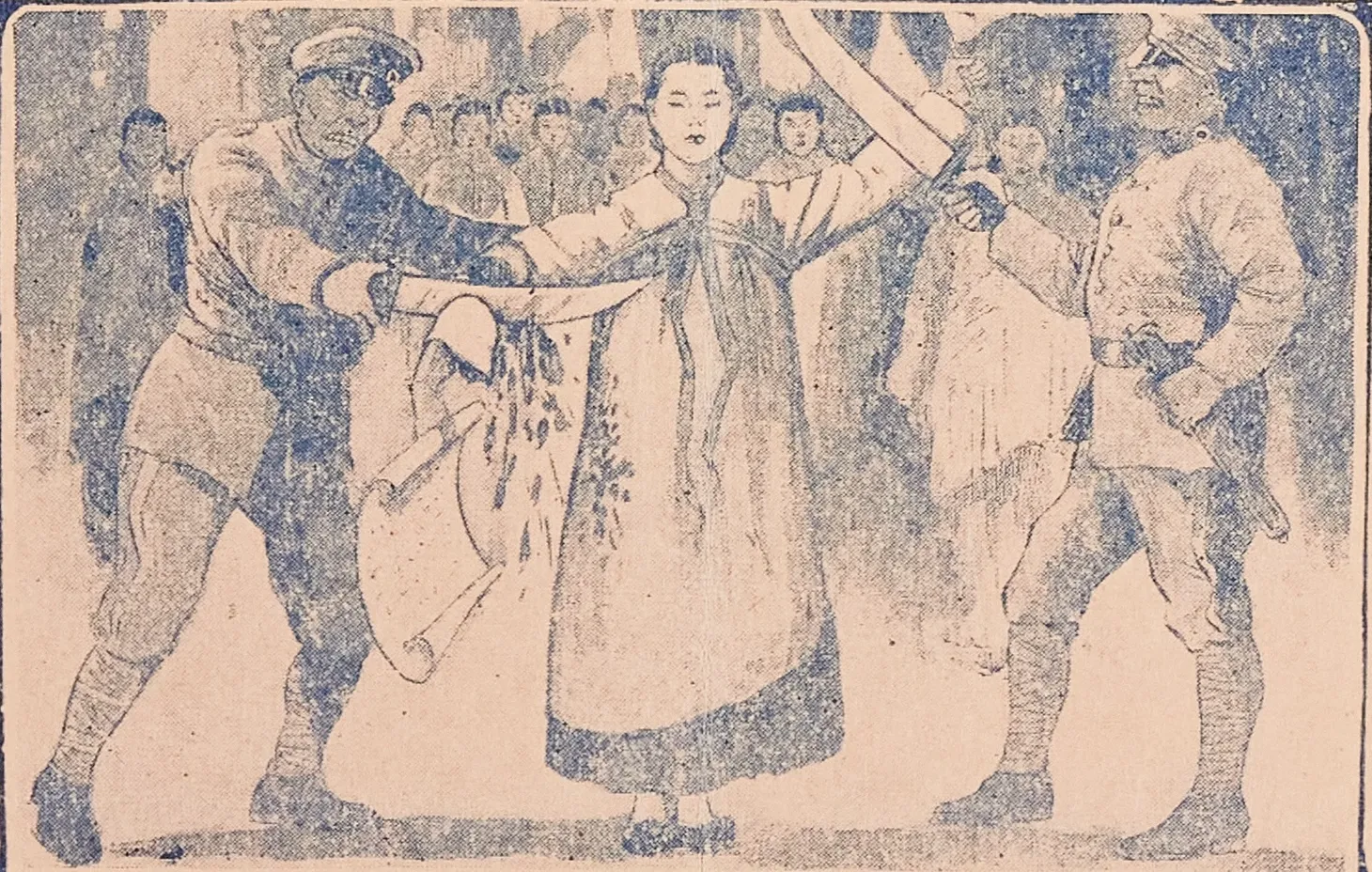

It is even more convincing to locate the opening guns of the long Second World War in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, an event that ended the short interbellum (1923–31) and prefigured other expansionist imperial responses to the Great Depression. The adoption of a start date of 1931 does not imply the outbreak of continuous warfare (Sino-Japanese hostilities were interrupted by the tenuous Tanggu Truce of 1934–7) but it does allow us to view a series of key events, including the German invasion of Czechoslovakia, the Italian occupation of Albania, the Spanish Civil War, the Japan–Soviet border wars and the Soviet–Finnish Winter War, as constitutive elements in an unfolding process of global conflict rather than simply preludes to world war…

With their intimate connection to the Sino-Japanese and Pacific wars, these events suggest that the Chinese Revolution was as much a constitutive element of the Second World War as the Russian and German revolutions were of the First World War. Moreover, in contrast to the harsh but rapidly resolved partition of Europe, fighting continued throughout the raggedunwinding of the war in Asia until the end of the deadlocked ‘police action’ in Korea in 1953 signalled the establishment of precarious regional stability…

Reframing the Second World War as a protracted process of conflict whose central paroxysm (December 1941 - September 1945) emerged from and unwound back into an extended series of regional wars (1931–53) helps to highlight its true globality. It also opens the door to integrating three key areas of investigation: first, it facilitates the incorporation of major areas of the world, including the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, that are often marginalized or omitted entirely from standard English-language accounts; secondly, it problematizes the categories of ‘pre-war’, ‘war’ and ‘post-war’, allowing us to think about uneven and combined processes of transition rather than simply passages from one steady state to another; and thirdly, it allows narratives of connectivity, transnational mobility, hybridity and environmental consequence to be accorded appropriate salience.

I like how these authors are looking for ways to reframe these wars as truly global wars, rather than European wars with global consequences. In both cases, the authors recognize the traditional dates for the world wars as periods of intense warfare, but they also believe we can’t understand these periods of intense fighting without situating them within a longer span of time. At the very least, we can ask students to consider these dates as potential alternatives to how we remember and periodize the world wars.

For teachers who want to truly rethink how we teach the first half of the twentieth century, we can treat both world wars as part of an extended period of conflict with many overlapping issues and themes. In The Origins of the Modern World: A Global and Environmental Narrative from the Fifteenth to the Twenty-First Century, Robert Marks uses the concept of a “Thirty Years’ Crisis.” On the OER Project, Trevor Getz prefers to describe the same period as “Global Conflict.” Both authors see the period between the wars more as a brief pause in fighting than as peace. The problem with these concepts is that the authors use the older Eurocentric dates for the wars.

Instead of beginning in 1914 and ending in 1945, we can synthesize the arguments above and think about a “Forty Years’ War” that started in 1911 and ended in 1953. We already have a well-established tradition of a Hundred Years’ War that lasted 116 years and a Seven Years’ War that lasted nine years when we include the North American theater. Why not have a Forty Years’ War that lasted forty-two years? By adopting this framework, we have a truly global approach to thinking about the first half of the twentieth century that begins with a conflict in North Africa and ends in the Korean Peninsula. Another benefit of this framework is that it pairs well with a truly global approach to the Cold War, emphasizing a conflict between competing ideologies of First World capitalism, Second World Communism, and Third Worldism. There’s no reason we need to treat twentieth-century African, Asian, Latin American, and Pacific history as sideshows to a traditional American-European-Russian narrative.

To help introduce this concept, I put together a seven-minute video that could be used with students.