“For the Right of Every People to Govern Themselves”: Challenging Empire in 1919

Discussion of how to teach 1919 as the start of decolonization.

In most world history textbooks, there is a section right after the First World War on the aftermath of the war. It usually begins with Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points speech. Most of the focus in this section is on the Paris Peace Conference: how it benefitted the British and the French, punished Germany, and the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires. Depending on the overall structure of the textbook, there might also be a little information on the Russian Revolution or the Influenza Pandemic of 1918 - 1920. At the end, there might be a final paragraph about the events in Egypt, India, Korea, and China during 1919.

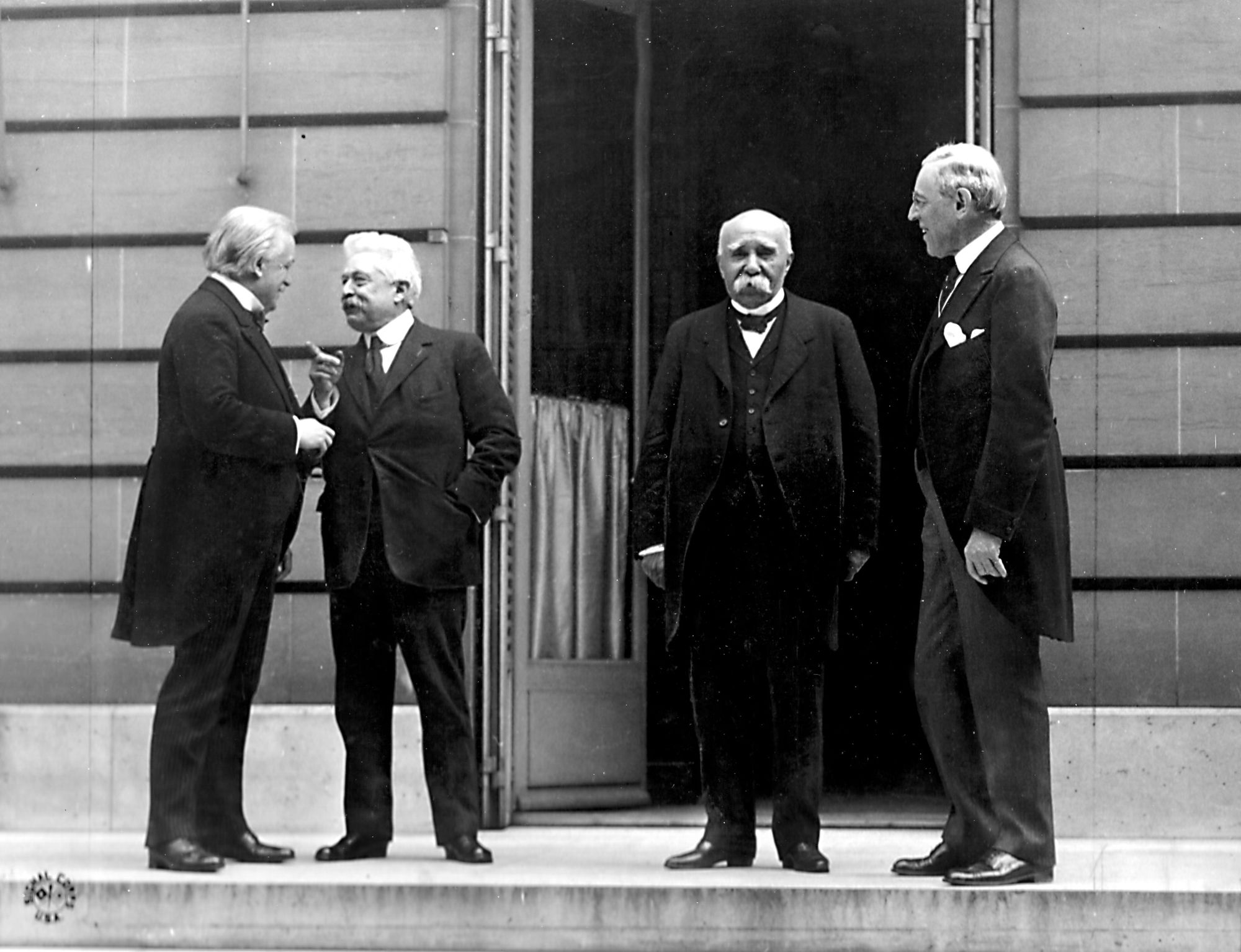

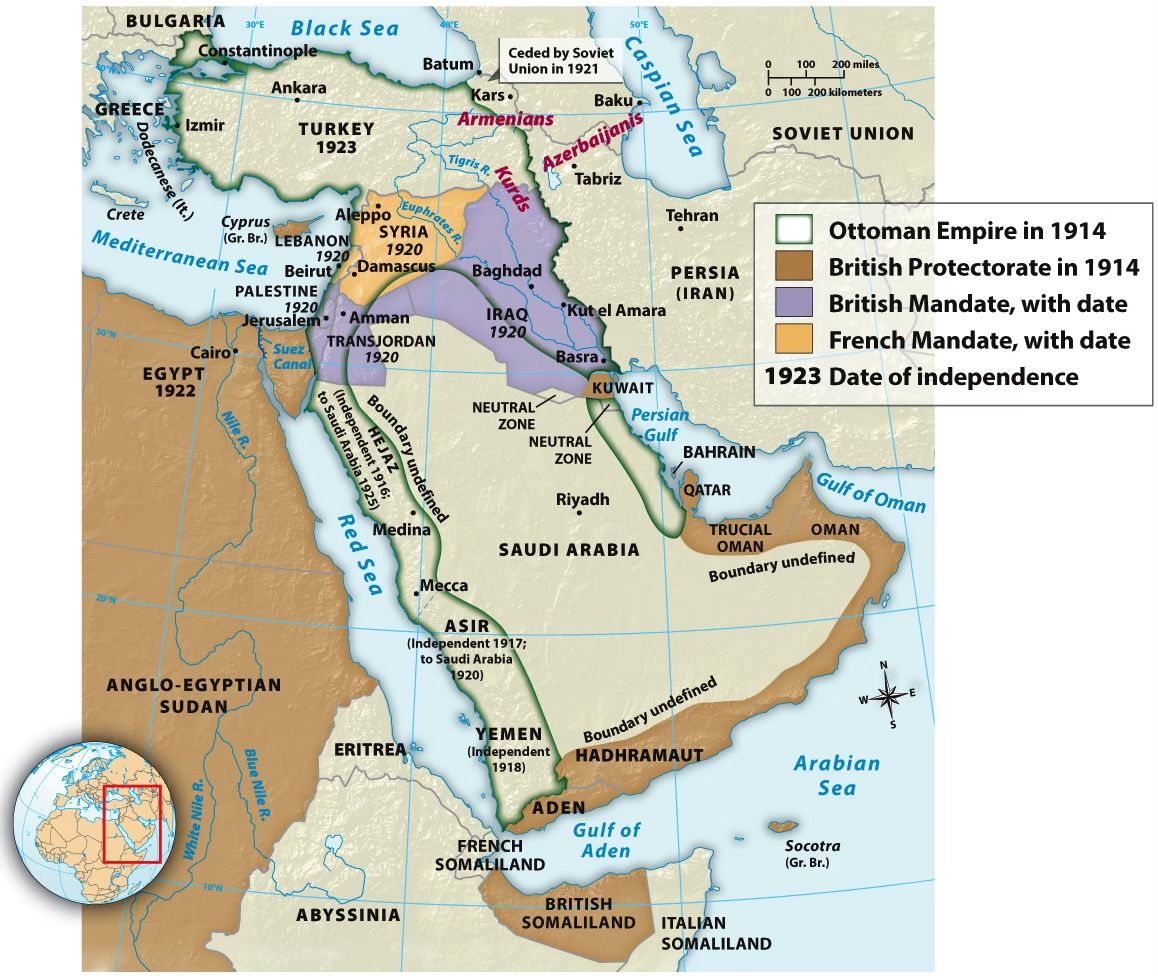

This standard narrative of 1919 mirrors how the American, British, and French leaders behaved at the conference. For them, they were meeting in Paris to focus on European affairs. They wanted to redraw the map of Europe and punish the losers in the war. Almost every textbook has maps showing how European and Middle Eastern borders changed between 1914 and 1923. For Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and Wilson, the concerns of Africans and Asians were an afterthought.

Left: Europe’s new borders. Source: Forging the Modern World. Right: The Middle East’s new borders. Source: A History of World Societies.

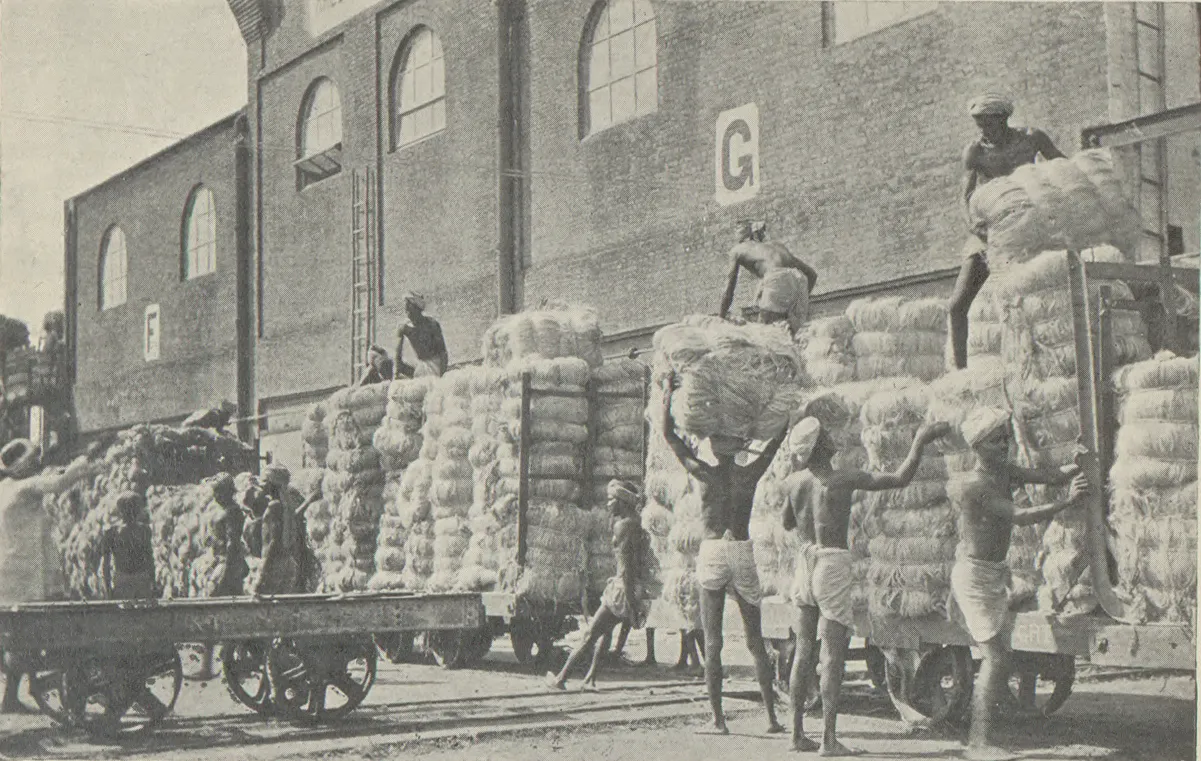

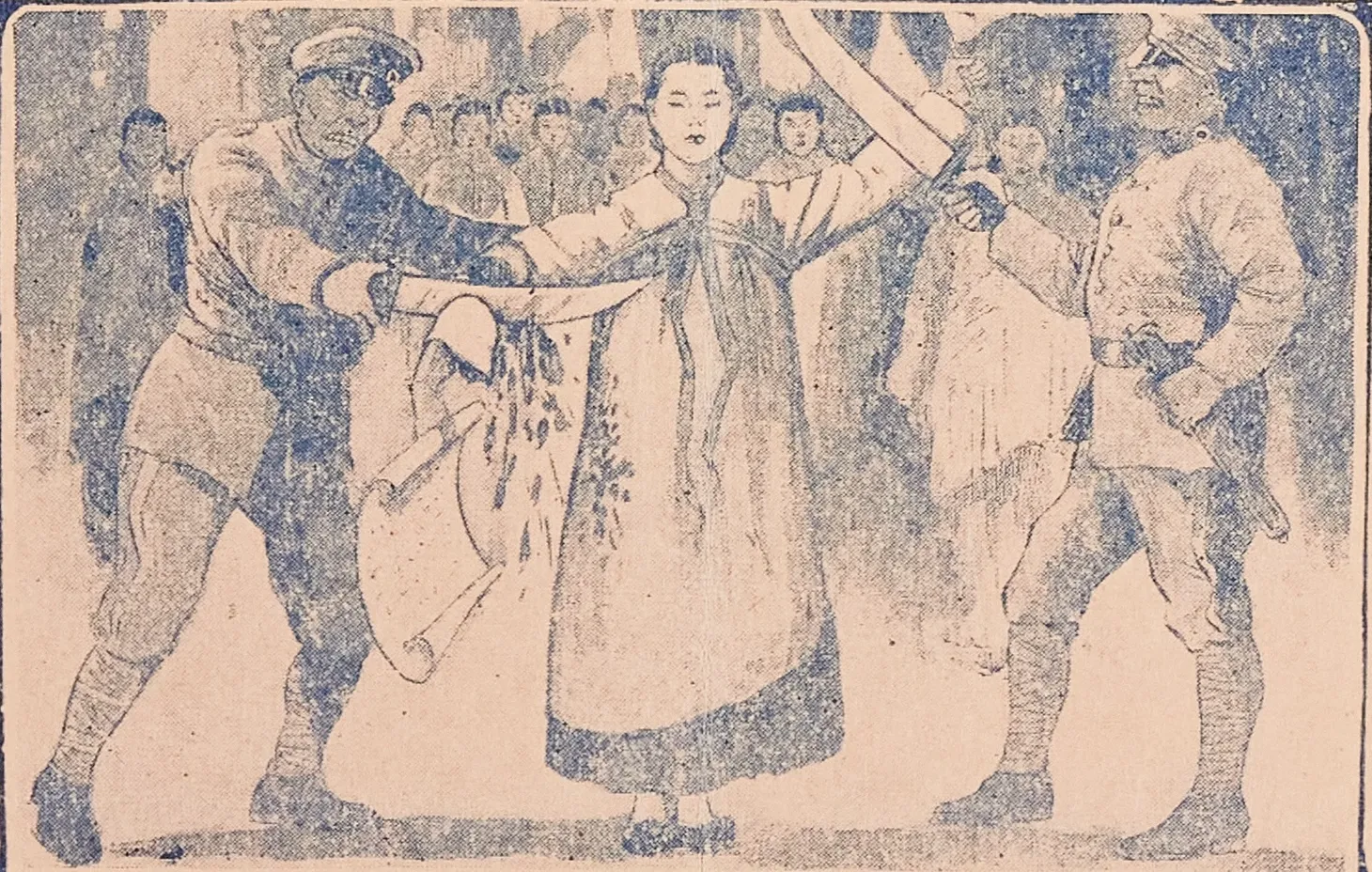

When I began teaching world history, I followed this standard narrative. Because I had been taught a Eurocentric vision of the First World War, it seemed more important to help students understand how the Paris Peace Conference punished Germany and set up the Second World War than to focus on how millions of people worldwide began to challenge imperialism. I previously discussed how reading Erez Manela’s The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism challenged me to rethink how I taught 1919 and the aftermath of the First World War. I realized I was recreating the Paris Peace Conference. Most of my focus had been on Europe. I only briefly mentioned the protests across Africa and Asia, what Manela calls the “Wilsonian Moment.” By focusing more on the demonstrations, students can better understand how millions of people began to question empire and demand political rights.

A quick note: In this post, I plan to share lots of short excerpts from textual primary sources and visual primary sources. One ideal way to use this material in the classroom is by having students do small research projects about the protests. Eric Beckman’s Global 1919: Paired Texts Lesson Plan is an excellent resource for putting together slogans for each protest movement and sharing them with the class. I will also include lots of further resources at the end of this post that can be used to help students learn some background about the different protests.

Petitioning and Protesting for Independence and Rights

This content is for Paid Members

Unlock full access to Liberating Narratives and see the entire library of members-only content.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in