“Men of the Spoken Word”: Teaching West Africa, c.1200 - c.1600

A discussion of the challenges of teaching medieval West Africa in world history courses and how to use voice of the griots as a way to explore multiple perspectives/

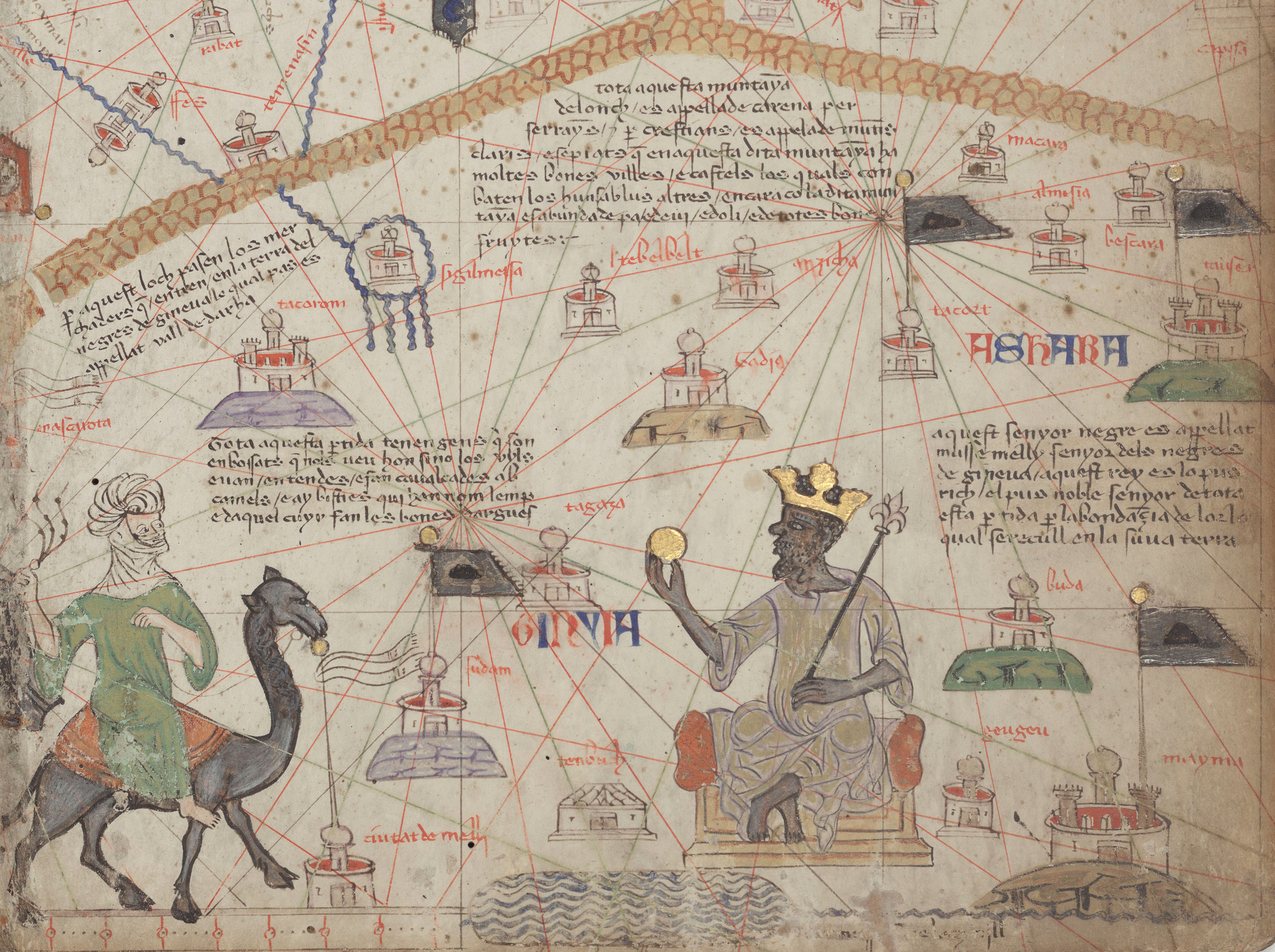

If you are reading this post, there’s probably a good chance that, like me, you have stood in front of a classroom teaching about the Empire of Mali and showing a picture of Mansa Musa from the Catalan Atlas. For twenty years, I always taught about the West African states of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay in my world history courses. I thought by just including these states and the Trans-Saharan trade, I wasn’t teaching a Eurocentric world history course. Over that time, I used different maps, primary source documents, and videos, but that image was always included. My students seemed to enjoy reading excerpts from Ibn Battuta to figure out what he was saying about the people of Mali. Looking back at those classes, I feel I could have done better.

As teachers, we know there’s always room for growth and improvement. We believe that for our students, but it also applies to ourselves. Over the last two years, I read a lot about West Africa and thought about how to put together more compelling classes for my students. I kept collecting new anecdotes and sources, but I struggled to find a way to put these resources together in a way that was fundamentally different from what I had been doing for so many years.

Last month, I was at Cape Coast Castle in Ghana, listening to my impressive guide Francisca tell stories about the horrifying dungeons in which enslaved Africans were kept. I felt many emotions, but I was also drawn to how she told those stories. Later that day, as I was processing what I had seen, I realized that her storytelling made the experience so powerful. It wasn’t just what she said, it was which parts of the story she chose to emphasize, where she chose to linger, and how she linked her own life to the experiences of those who came before her. I then had similar experiences with guides at Elmina Castle and the House of Slaves on Gorée Island in Senegal.

These experiences showed me that the problem with my classes on West Africa was that a certain kind of storytelling was missing. This is especially problematic since griots play an essential role in how people from West Africa understand their history. Reflecting on how we teach the history of West Africa between 1200 and 1600, we want to make sure that we balance our wealth of material from outside the region with an understanding of how people from these West African states understood their world. In short, we must keep asking ourselves and having our students ask, “what would the griot say?”.