More than Four Turtles: Global Renaissances in the Fifteenth Century (Part II)

Table of Contents

In the final part of the Harkness discussion on Day 3, we talk about the second part of my essay “Reimaging the Renaissance,” which focuses on events in Central Asia in the fifteenth century.

Central Asia never seems to get the credit it deserves in world history classes. Besides the Mongols, we almost always seem to skip over the region. For example, I’ve talked to many teachers and students who are convinced that the Silk Roads were more about the Roman and Han Empires than the huge amount of territory in between them. (For a good discussion on viewing the Silk Roads from a Central Asian perspective, check out David Christian’s great article “Silk Roads or Steppe Roads? The Silk Roads in World History”.) After traveling across Central Asia in April and May of 2016, I knew that I needed to develop some more lessons that focused on Central Asia. I remember sitting in front of the Registan in Samarkand and realizing that the first of these three incredible madrassas had been built at the same time the Renaissance was happening in Italy. It was over the next couple weeks that the outline of the essay at the end of this post took shape. I wanted something that would introduce this incredible Timurid Renaissance to students and present them with the ideal comparison to the Italian Renaissance.

In the essay, I provide a basic overview of Timur (the students have already learned a little about him during the previous two classes) and the empire he founded, Timurid architecture, the interest in astronomy and mathematics, Persian miniature painting, and Chaghatay literature. I also frame this cultural movement as occurring at the same moment as the Italian Renaissance. By looking at the Timurid Renaissance alongside the Italian Renaissance, we can begin to see how “these periods of rich intellectual and cultural development were not uniquely a European phenomenon. In both cases, these developments came about because of the interaction of peoples from different backgrounds. Timur’s empire linked together people from Central Asia, the Middle East, and South Asia, with links to western China, while the Renaissance was the product of increased interaction of Italian peoples with Muslims of the eastern Mediterranean. In many ways, these two movements reflect the increasing global interconnectedness of the Early Modern era in world history.”

This part of the class is usually filled with students expressing surprise at having never heard about Timur or the Timurid Renaissance. After that initial surprise we move into a broader discussion of how we make sense of these three Renaissances (Strayer’s Italian Renaissance, my Mediterranean Renaissance, and the Timurid Renaissance). I love watching how students compare the different arguments and develop their own understanding of a more global Renaissance. The better students are also able to connect these readings to the ones from earlier in the week on Afroeurasian political and economic revivals, as well as earlier ideas from the course about competing visions of world history and how we can get beyond Eurocentric interpretations of world history.

I think back to those discussions about the Renaissance that began ten years ago on the AP World History listserv, and I finally feel comfortable with teaching about the Renaissance in world history courses.

“The Timurid Renaissance”

To problematize the older notion of the Renaissance as a uniquely European and modern event even further, we can look at Central Asia from the late fourteenth to the early sixteenth centuries. During this period, the Turkic warlord Timur (1336–1405) conquered widely across Central Asia, the Middle East, and South Asia and established the Timurid Empire which oversaw an intense period of cultural flourishing. This Timurid “golden age” also happened simultaneously as the European Renaissance. Peter Golden, a Central Asian historian, argues “that the Timurids, with their emphasis on promoting culture and meritocracy, were like the Renaissance monarchies of Europe in which cultural displays became essential parts of governance.” 1

Timur had been born in 1336 near modern Shahrisbaz, Uzbekistan, which was part of the Chagati Khanate, one of the Mongol Khanates. During his early life, the Chagatai Khanate and the neighboring Middle Eastern Ilkhanate collapsed. Timur stepped into this void, secured a numbered significant military victories, and assembled a large empire between 1370 and 1405. His wide-ranging victories resulted in a diverse group of artisans and scholars becoming concentrated in his capital Samarkand. Some of these individuals were prisoners of war, while others came by choice. This diverse group, and subsequent arrivals, interacted with each other and contributed to important developments in arts, architecture, sciences, and language that would typify the Timurid Renaissance of the fifteenth century. 2

During Timur’s lifetime, he began an ambitious building program. He began with turning the town of his birth, Kesh, into a showpiece capital. He renamed the town Shahrisabz, “The Green City.” The main palace was the Akserai (“The White Palace”), which was a massive palace complex that could be seen from twenty-five miles away. He also built a massive mausoleum for Ahmad Yasawi in Turkestan and the large congregational mosque in Samarkand, known as the Bibi Khanum mosque. These buildings were not only noted for their large size, but also for their distinctive architectural style involving expansive arches and distinctive domes.3

His descendants continued Timur’s architectural legacy. The famed Registan in Samarkand is a large public square. Timur’s grandson Ulugh Beg, and ruler of Samarkand, built the Ulugh Beg madrasa, which became the premier center of learning in the fifteenth century Muslim world. Around the entrance, visitors were greeted by the Hadith “To strive for knowledge is the duty of every Muslim.” Later rulers of Samarkand added additional madrasas to the Registan, and the square served as important center of learning in Central Asia for centuries. Also in Samarkand, Timurid’s descendants and followers built the Shah-i-Zinda, a large complex of mausoleums. Although these mausoleums were smaller than the madrasas and palaces more frequently associated with Timurid architecture, the style is similar in the use of of arches and domes. It was this distinctive combination of architectural features, concern with the geometrization of design, and brilliant colors that came to define Timurid architecture, which continued to dominate Muslim architecture across much of Central Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East for centuries.4

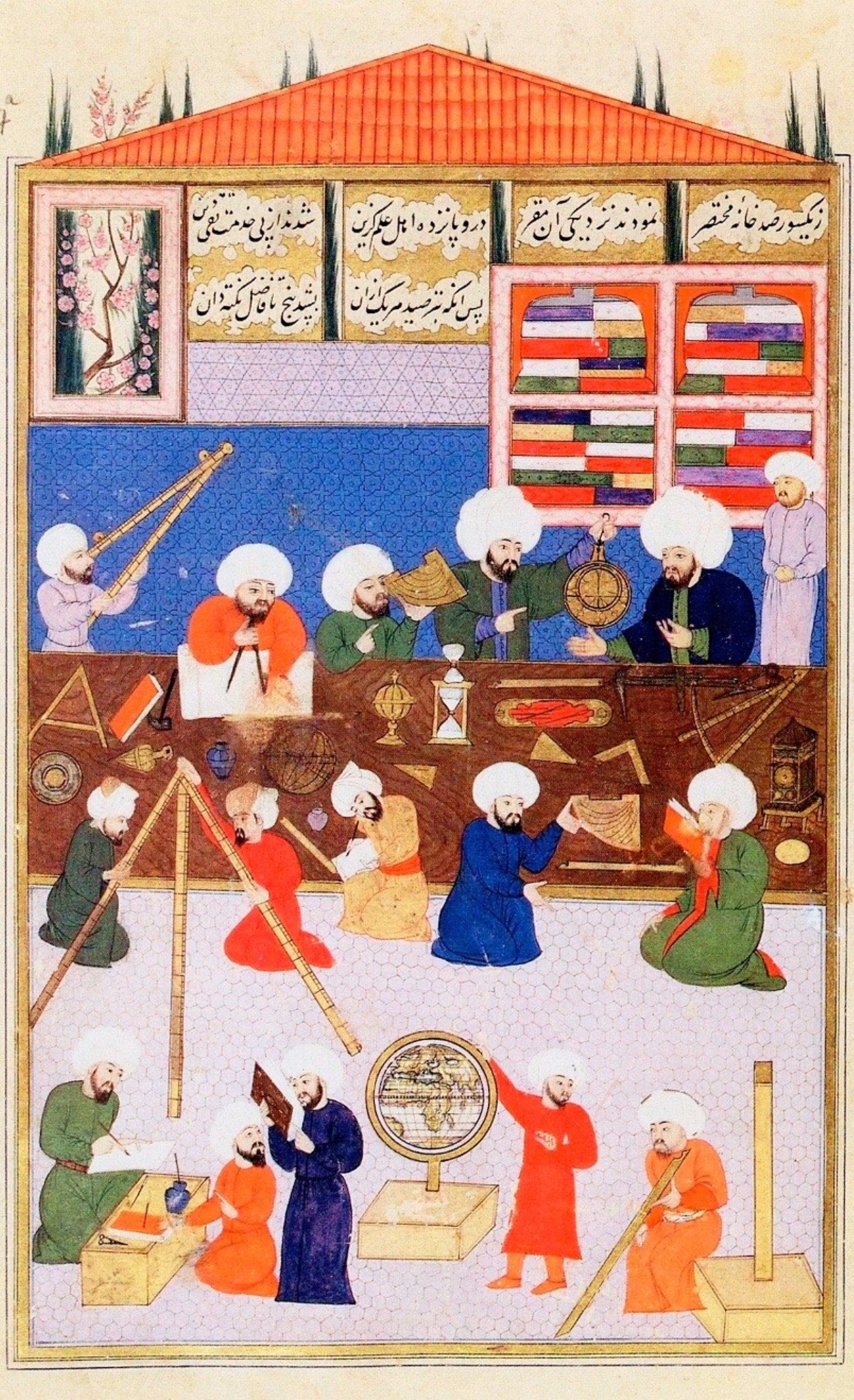

Throughout the fifteenth century, Timurid Central Asia also became famous as a center of learning, especially in mathematics and astronomy. While there were many small madrasas and observatories built, none were more famous than Ulugh Beg’s observatory just outside the city of Samarkand. The massive three story complex was crowned with a brass sextant with a radius of more than 100 feet. Astronomers at the observatory set out to record the exact location of all the major stars. Their findings were recorded in the Zij, a collection of astronomical tables. The observatory and the star catalog reflected a similar concern with precise observation and recorded data in Europe among scientists and astronomers at the same time. The work of the astronomers at the Ulugh Beg observatory would be shared across the Muslim world. Subsequent observatories in South Asia and the Middle East also copied the design of the Ulugh Beg observatory.5

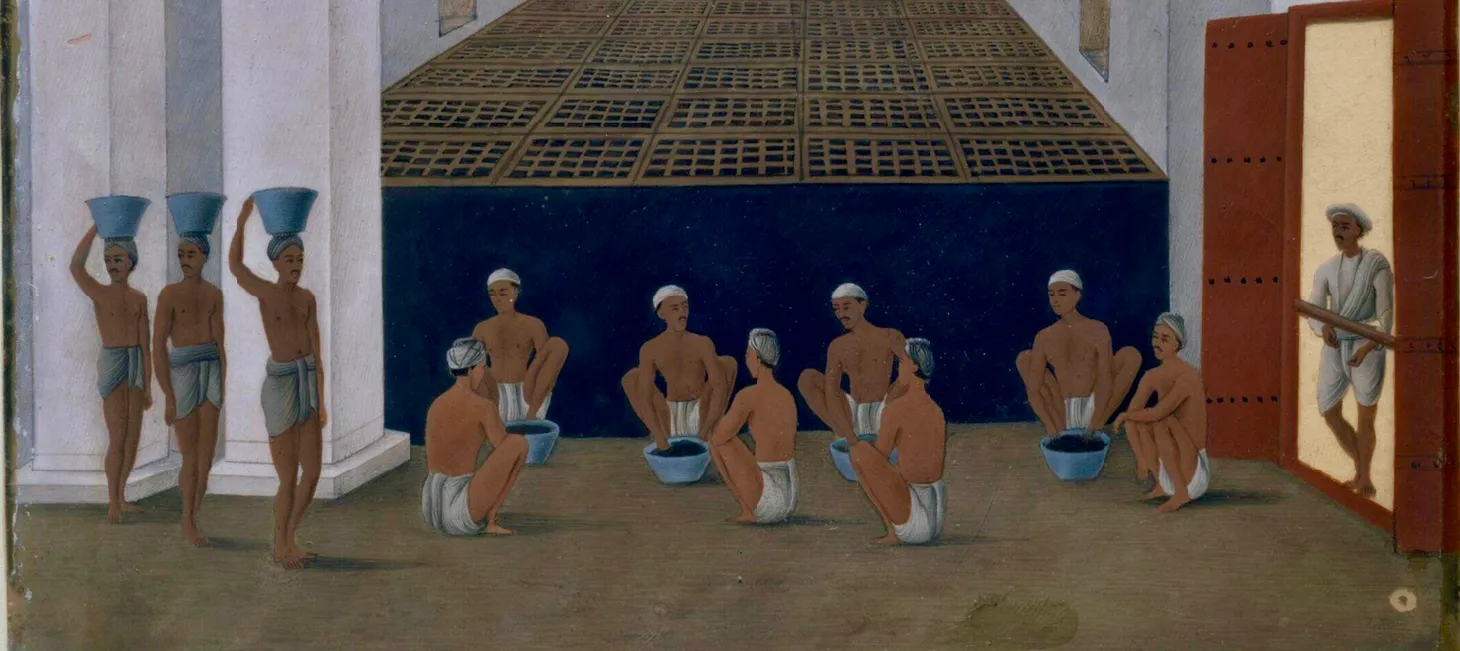

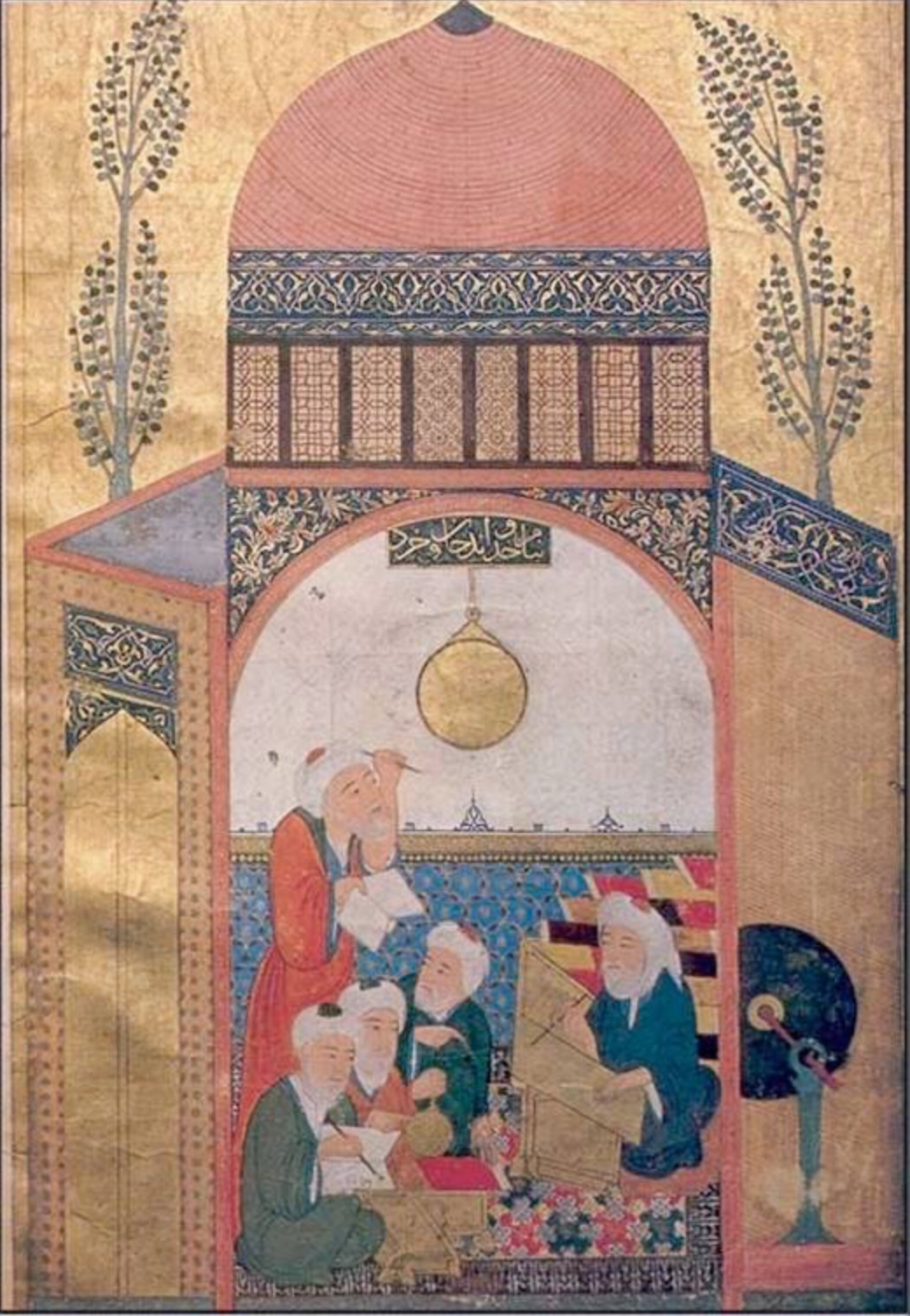

In addition to these advances in architecture and astronomy, the Timurids also contributed to a flourishing of a distinctive style of miniature painting and the development of a new literary language. Beginning in the thirteenth century in Persia, miniature painting in manuscripts became more common. During the Timurid era, the numerous scientific, historical, and literary texts being produced in Central Asia led to a proliferation of a distinctive style of illuminations that was then spread back to Persia and to India. The development of Chaghatay as a language also reflected the rich culture of the Timurids. Chaghatay was a local Turkic language, and poets such as Navai wrote in that language. Chaghatay quickly displaced Persian as the literary language of Central Asia.6

The combination of important developments in architecture, learning, astronomy, painting, and poetry during the Timurid period of the late fourteenth to early sixteenth century – the same time frame as the Renaissance in Italy – suggest that these periods of rich intellectual and cultural development were not uniquely a European phenomenon. In both cases, these developments came about because of the interaction of peoples from different backgrounds. Timur’s empire linked together people from Central Asia, the Middle East, and South Asia, with links to western China, while the Renaissance was the product of increased interaction of Italian peoples with Muslims of the eastern Mediterranean. In many ways, these two movements reflect the increasing global interconnectedness of the Early Modern era in world history.

Liberating Narratives Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.