“Organizing the Rice Fields”: Teaching Southeast Asia’s Nineteenth-Century Production Revolution

Discussion of how to teach Southeast Asia’s economic changes in the nineteenth century

The first time I visited Southeast Asia, I fell in love with the rice terraces. I remember hiking through the Sa Pa Valley in northwestern Vietnam in the summer of 2002 and wondering how these beautiful and elaborate terraces were built and maintained. I vaguely remembered the phrases “Oriental despotism” and “Hydraulic empire” from graduate school, but I knew they were problematic. States never had as much true power as historians imagined. During that summer, I was restructuring my world history curriculum, and I remember being disappointed about how the books I was reading said little about Southeast Asian rice. Besides the early history of rice cultivation, including every world history teacher’s favorite illustrative example of Champa rice, most textbook authors gave the impression that European colonizers forcibly integrated Southeast Asian rice into the world economy in the late nineteenth century.

Strayer’s Ways of the World was the first textbook I remember using the phrase “pull of the market” to describe how small farmers in British Burma chose, rather than being pushed, to produce rice for export. This phrasing led me to Michael Adas’ classic The Burma Delta: Economic Development and Social Change on an Asian Rice Frontier, 1852–1941. When my eyes weren’t glazing over from the pages of economic statistics and tables, I loved the anecdotes about how growing rice for export transformed the Irrawaddy Delta and the lives of farmers. He described farmers’ houses that “commonly contained European furniture, mirrors, artificial flowers, gramophones, English lamps, looking glasses, metal safes or chests, and clocks.” If I could find a way to excerpt some of his arguments, here was a way to help students understand colonized peoples’ agency in the late nineteenth century.

Over the years, I kept tweaking how I taught about Southeast Asia’s participation in the world economy in the nineteenth century, but I never felt happy with my lessons. (And students unsurprisingly were not interested in tables of Southeast Asian rice production and export.) Something was missing. I realized I needed to stop discussing Southeast Asia’s participation in the world economy and start talking more about Southeast Asians’ participation. Regions don’t produce things; people do. We must keep those people in mind when we’re teaching economic history.

Left: Southeast Asia in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Right: Southeast Asia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Both maps are from O'Brien's Atlas of World History.

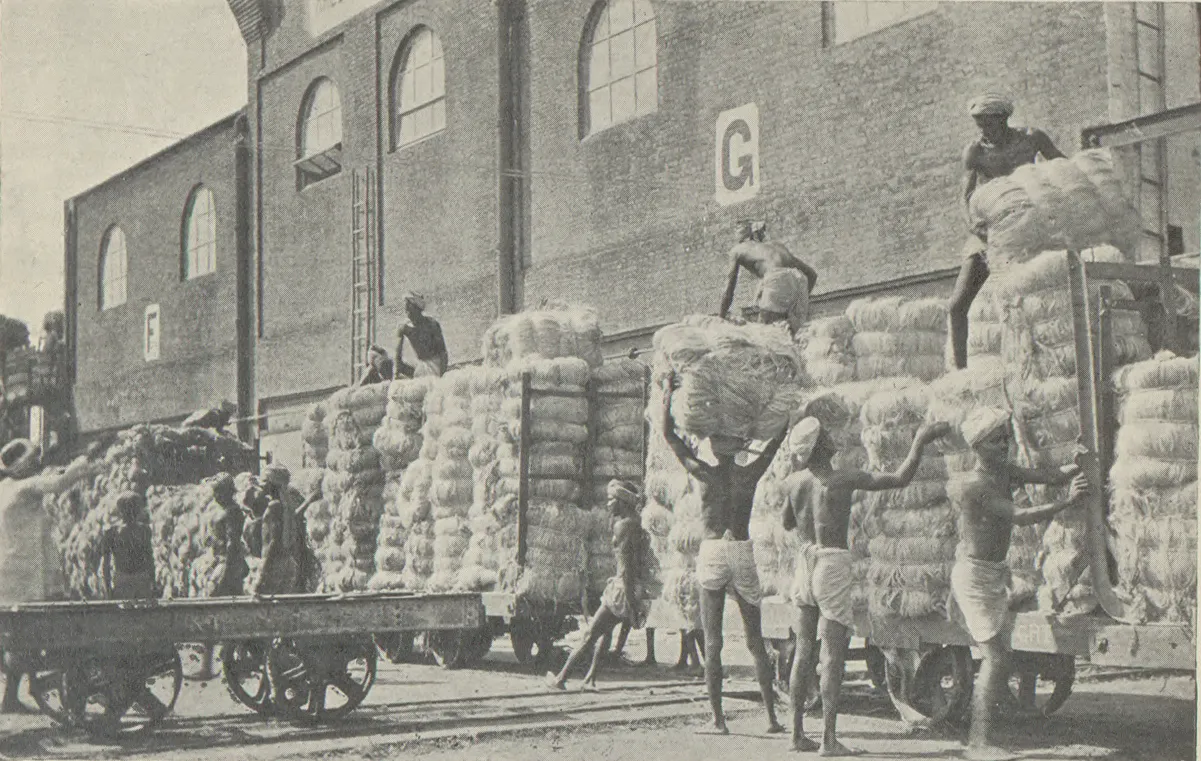

Like the Egyptians, South Asians, and West Africans I’ve been discussing recently, Southeast Asians participated in a production revolution during the nineteenth century. While there was less transformation of how crops were grown, millions of Southeast Asians began growing rice and other crops for export to the global market. While European colonizers helped facilitate this transformation, we want to emphasize how local and regional actors remained integral to this process.

Making Singapore Bloom: The Surprising Story of Gambier

This content is for Paid Members

Unlock full access to Liberating Narratives and see the entire library of members-only content.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in