“Peace Was Made with the Carios”: Snapshots from Indigenous American History

A discussion about integrating the experiences of Indigenous Americans into the teaching of world history.

In the past month, I’ve had a surprising number of conversations about failure. As teachers, most of us want to avoid failing. We don’t like seeing our students fail, and we don’t like our own failures. The problem with continually trying to avoid failure (i.e., being a perfectionist) is that we learn by making mistakes. When we realize we have made a mistake, we have an opportunity to acknowledge the error, to apologize if we’ve hurt others, and to address the mistake. We need to normalize talking about learning from failing to help our students, our colleagues, and ourselves.

When I look back at some of my earlier posts, I see my failures, and they are scary. Since I converted Liberating Narratives from an occasional blog to a weekly newsletter, I have avoided writing about how we can teach the history of Indigenous Americans in our world history courses. My avoidance has partially been because of my mixed feelings about “‘People Who Have Interrupted Empire’: African and Indigenous Resistance in the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries,” a post I wrote almost three years ago. I appreciate how the post highlighted the problems with discussing “conquest” in the sixteenth century, but I’m disappointed with how I discussed resistance. There are too many underdeveloped examples of resistance, and I only focus on large-scale acts of resistance, such as uprisings and rebellions.

Instead of going back and editing the post, I want to turn my failure into an opportunity for growth. I spent the last few months reading more about the history of Indigenous Americans (when I use this phrase, I mean indigenous people in all the Americas, not just the United States) and learning from more knowledgeable colleagues about this topic. I’ve learned that in many world history textbooks, we find lots of information about conquest, a little about resistance (the large-scale kind), and almost nothing about adaptation.

During the next month, I plan to borrow from the framework of my earlier posts on the Ottomans and the Mughals and focus on a handful of snapshots to explore how we can better teach Indigenous American history in our world history courses. Instead of focusing mainly on conquest when talking about Indigenous Americans, I will discuss how we can highlight the persistent examples of resistance, both large-scale uprisings and small-scale acts of individual resistance, over the last 500 years. More importantly, I plan to explain how we can weave stories of indigenous adaptation into the “regular” topics we teach about in world history. When we focus more on how Indigenous Americans adapted over time, students can see how they had agency.

I’m not a specialist in Indigenous American history. I know I will make more mistakes in these posts, and I look forward to colleagues helping me learn from my errors. Even knowing I will make mistakes, I want to share these ideas about decolonizing our teaching of Indigenous Americans in world history. We owe it to our students, who deserve a more nuanced world history with a greater range of voices. Even more significantly, we owe it to millions of Indigenous Americans, whose voices and stories have too often been left out of standard narratives.

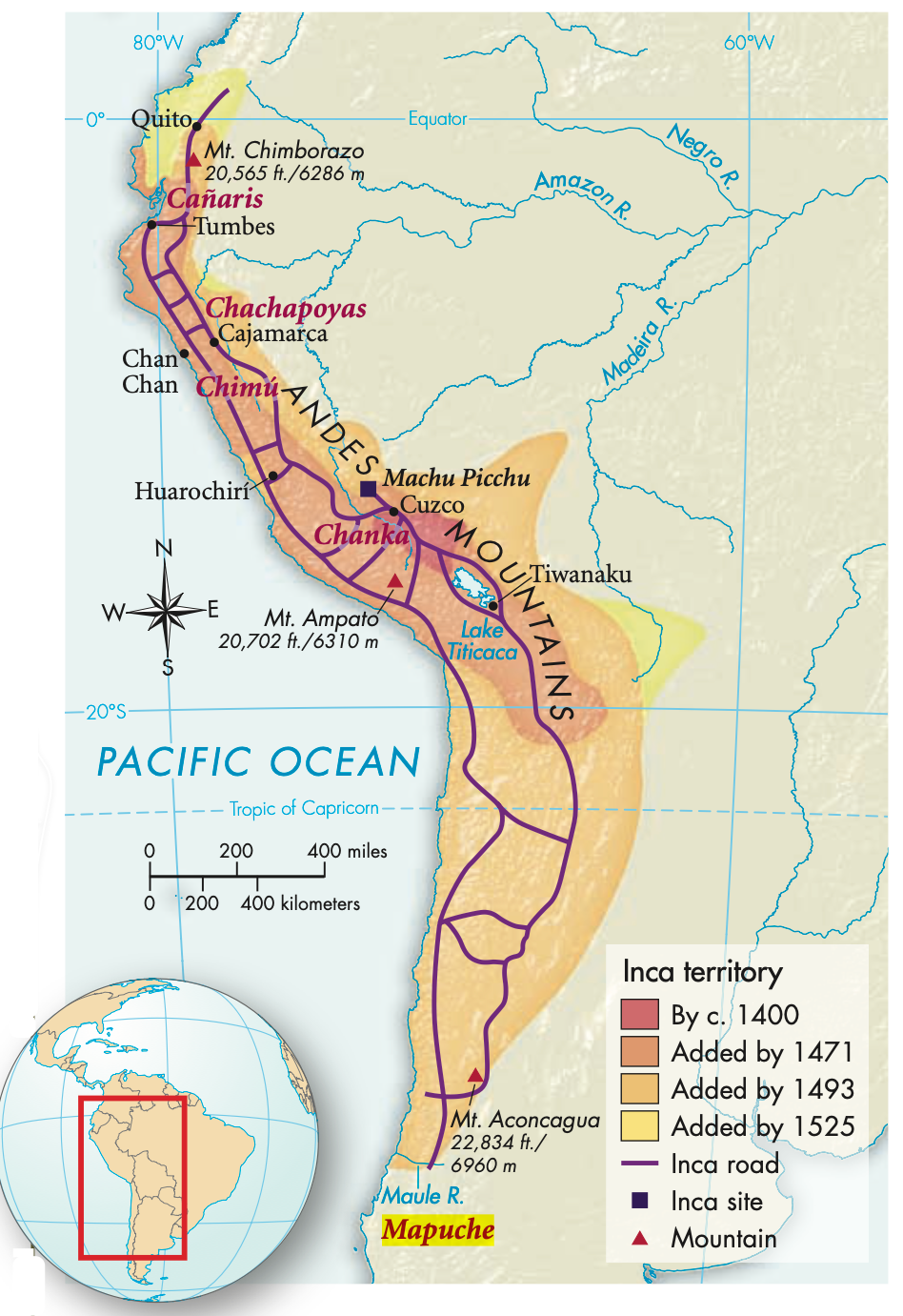

Resistance and Adaptation Among the Mapuche in Sixteenth-Century Chile