“We Set Sail in Search of New Spain”: The Forgotten Folks Who Made the Manila Galleons Possible

Discussion of teaching the contributions of Africans, Asians, and Indigenous people to the development of the Manila galleons trade route.

I never liked timelines. Many history teachers have students make or look at timelines, but that assignment never intrigued me. I understand the importance of having a sense of chronology, but I always thought having students make a timeline was a waste of time (pun intended). One year, I had a colleague who loved timelines and believed we should spend more time having students make their own timelines in world history. I didn’t want to be that stubborn older teacher who refused to try new things, so I agreed to a timeline project.

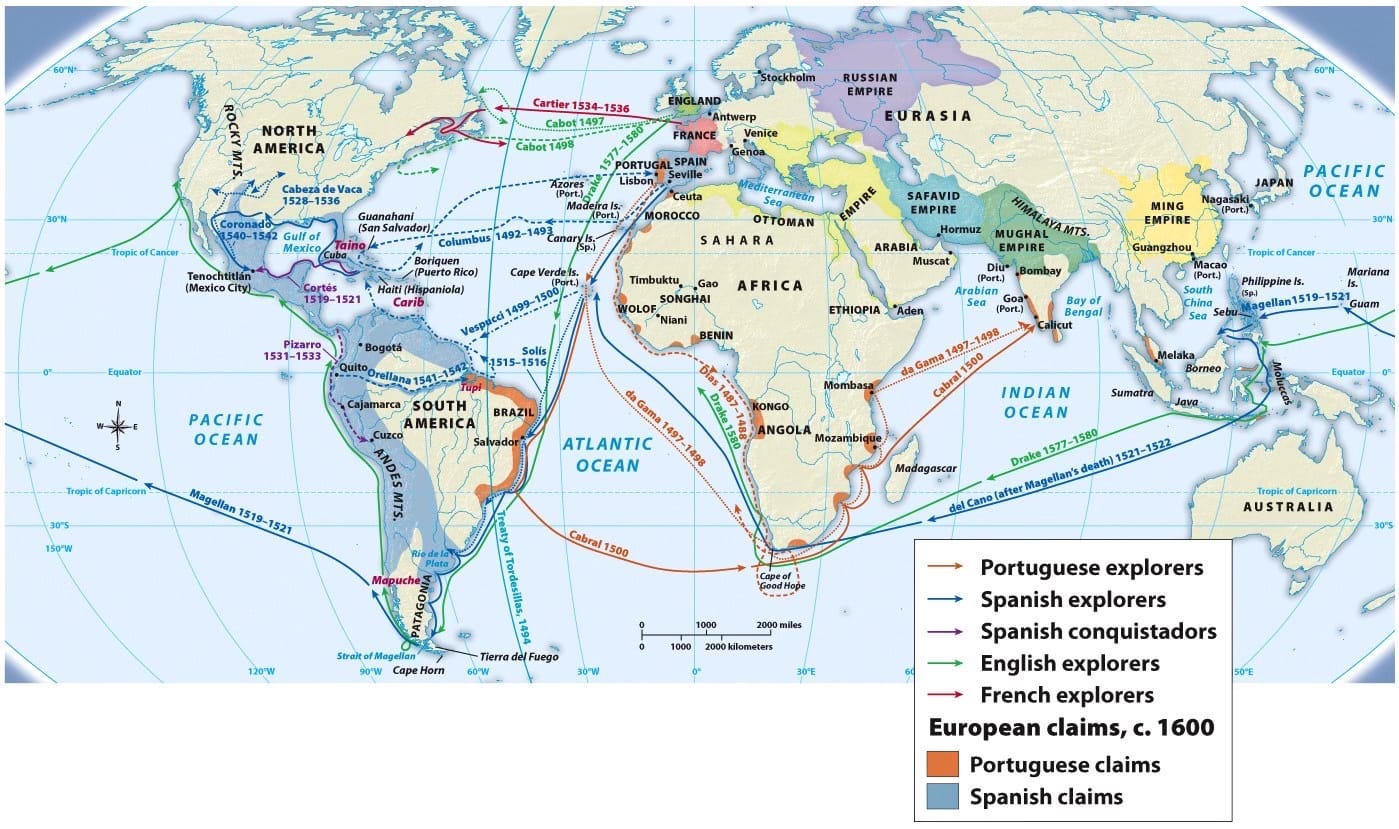

Students developed their own timelines for the early modern period. All the major European maritime navigators were there. I wouldn’t let students call the period from 1492 to 1600 the “Age of Discovery” (I’m sure the Indigenous Americans love knowing Columbus discovered them), but we did use the phrase “The Age of Maritime Connections.” I think it’s a more neutral phrase and focuses more on what we care about in world history. After looking at seventy timelines with Magellan circumnavigating the Earth in 1521 (spoiler alert: he didn’t circumnavigate the globe in a single voyage) and the start of the Manila galleons in 1571, I began wondering what happened in the intervening fifty years. Why didn’t the Spanish start trading across the Pacific sooner?

Answering my question led me to some surprising “discoveries” of my own. (Just because I recently first learned about these topics doesn’t mean I discovered them.) My first realization was that an enslaved man from Southeast Asia might have been the first to circumnavigate the Earth. My second realization was that the fifty-year gap between Magellan’s “circumnavigating the Earth” and the “start of global trade” wasn’t due to a lack of effort. The Spanish tried three times and failed three times to sail back across the Pacific from the Philippines to the Americas. And the man who first navigated across the Pacific to the Americas was an Afro-Portuguese mulatto whom Spaniards attempted to discredit. My third realization was that the Spanish “conquest” of the Philippines and the foundation of Manila between 1565 and 1571 depended a lot on the contributions of enslaved Africans, Indigenous Americans, and Filipinos. These new pieces of information made me realize that the transition from Magellan sailing across the Pacific to the birth of global trade involved many more people than we usually think about.

The First Circumnavigator: Magellan or Enrique of Melaka?

This content is for Paid Members

Unlock full access to Liberating Narratives and see the entire library of members-only content.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in