“Workmen Constantly Employed”: Teaching Mass Production and Industrialization in the Long Nineteenth Century

A discussion of how to teach the nineteenth-century Industrial Revolution as a global process.

When I began teaching world history, the Great Divergence was a popular topic for many historians. Everyone had a different potential cause of British industrialization and why some Western European economies industrialized before the rest of the world. I enjoyed having my students engage with this debate, and my first publication was on “Teaching the Great Divergence.” In 2004, I jumped at the opportunity to spend a summer in the English Midlands (my two English colleagues thought I was crazy), participating in an NEH seminar for teachers on “Historical Interpretations of the Industrial Revolution in Britain.” We visited many historic industrial sites across England. I remember being surprised by how small many early factories and mills were. In my mind, I was imagining the illustrations of late nineteenth-century factories, but sites such as Coalbrookdale seemed relatively quaint.

The following summer, I traveled across China and visited Jingdezhen, the “porcelain capital” of China. The Ming and Qing imperial porcelain factories were in Jingdezhen. After England, I was expecting something equally small but was shocked by the extent of the workshops and the size of the kiln. Those two trips challenged how I thought about industrialization. I realized that industrialization was a little less revolutionary than the name implied. Mass production in the late 1700s looked quite different from mass production in the late 1800s. I also understood that mass production did not begin with British industrialization.

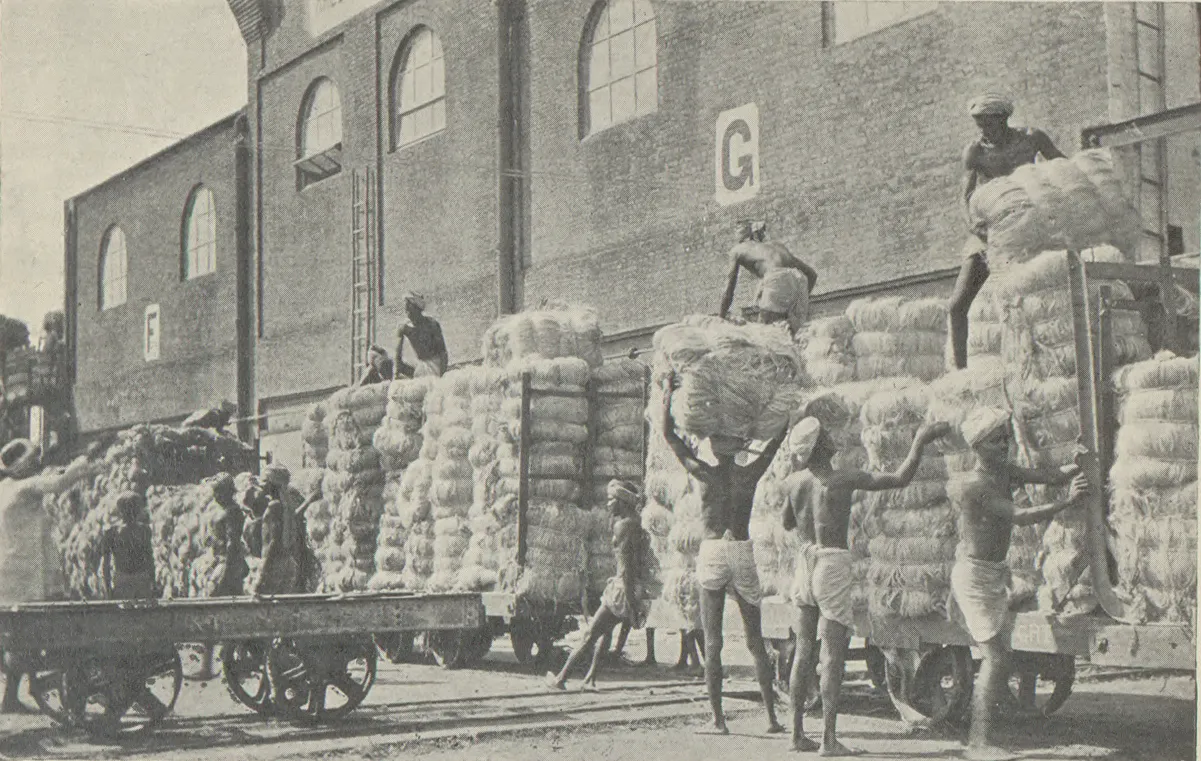

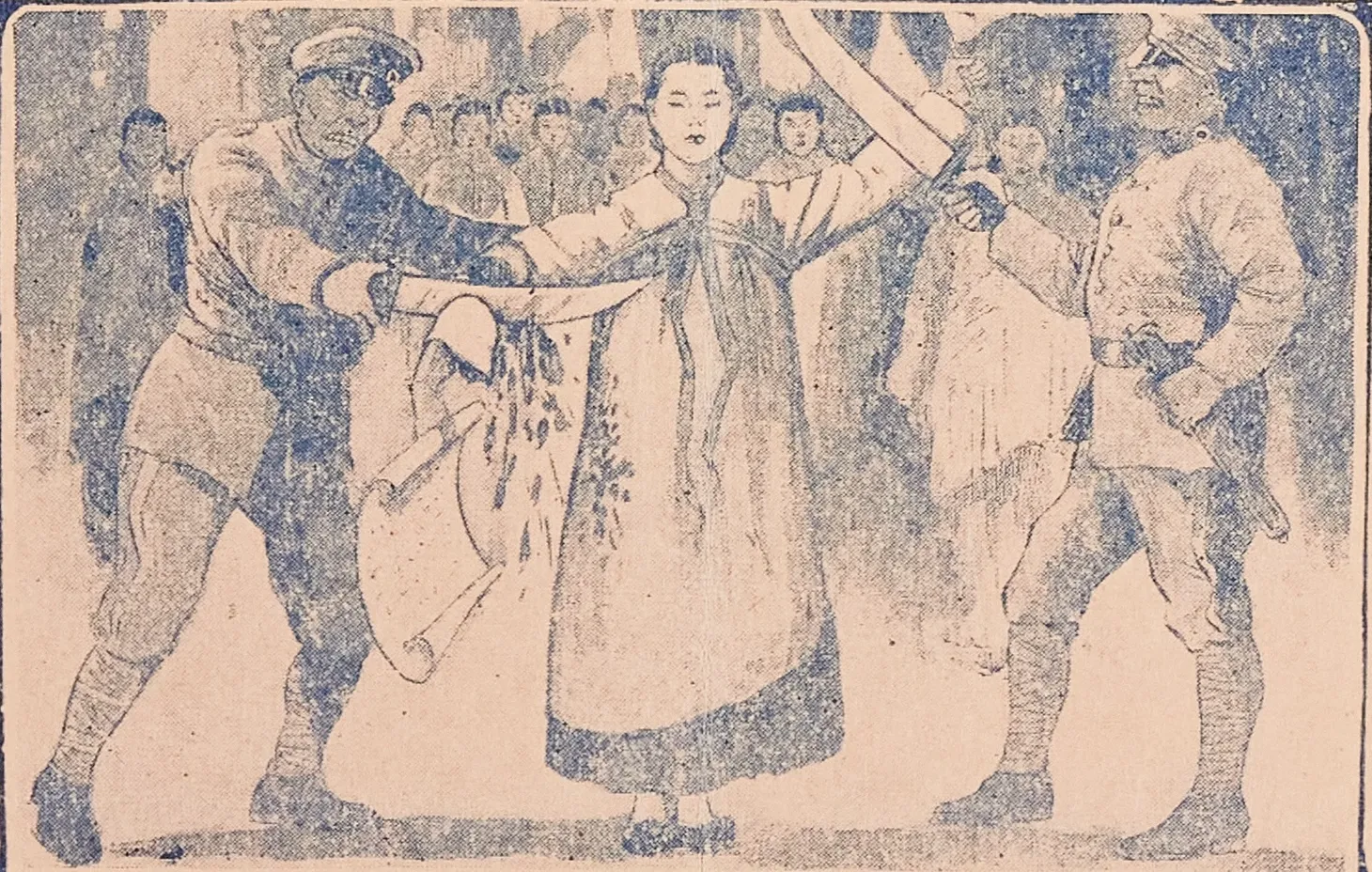

Over the next month, I will focus on how we teach the Industrial Revolution from a more global perspective. By exploring how other societies engaged in mass production in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, we can help students understand how those societies both influenced and were influenced by British industrialization. Students can see how “unindustrialized” regions also revolutionized the production of crops and goods in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Instead of thinking about the Industrial Revolution as a uniquely Western phenomenon that radiated outward from Britain, we can begin to see a more global production revolution.